The most dismaying part of today’s public policy dysfunction is the willingness of people who know or should know what they’re saying, which isn’t true, to shape views to align with their group’s views rather than look at the actual data. Just this past week, two well-known sources of information said things unsupported by any facts. If you believed them, it could cause harm.

On his Fox business show, Larry Kudlow and the panel laughed at a Wall Street Journal article showing professionals selling while the public buys. With the market rallying, their clear implication was that the public is smarter than the professionals and buying now is a better bet than selling.

This assessment flies in the face of experience. One of the universal signs of a market top is widespread bullishness, especially among smaller investors. Small investors don’t have the information that the pros have access to. Who else is left to buy to increase prices when the public is all in? Basing your market outlook on the supposed stupidity of professionals and the bullish actions of the public hasn’t worked out well in the past.

I don’t know what will happen. If the tariffs stay high, it’s hard to see a solid future. However, if Trump makes a few inconsequential deals, like the one with the U.K., and then calls most of the tariffs off, it would surely improve the outlook. At this point, no one knows what Trump will do. I don’t think Trump knows.

Having served in both the Reagan and Trump administrations, Kudlow has a unique position. He knows the adverse effects of high tariffs well, so it’s baffling that he’s taken a bullish position with high tariffs still in effect. Implying that the pros do less well at market turns than the public to justify his pro-Trump position is out of place.

I’ve thought of Fareed Zakaria, the CNN host and longtime Washington Post columnist, as providing a window into the thinking of the left-of-center intelligentsia. That’s why I noticed his note in his column this week: “It is worth noting, however, that the math is clear: Tax cuts are responsible for the vast majority of the increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio over the last 25 years.”

This claim underlies much of democratic thinking. How often has Barry Sanders said we can fix things if only “the rich pay their fair share.” Biden and others say the same thing. The problem is that this contention has no basis in experience:

As this chart shows, whether we raise taxes as we did under Roosevelt, the elder Bush, Clinton, and Obama, or cut them under Reagan, the younger Bush, and Trump, Federal receipts since World war II as a percentage of GDP varied only a point on either side of 17.5%. People change their behavior to adjust to tax policy.

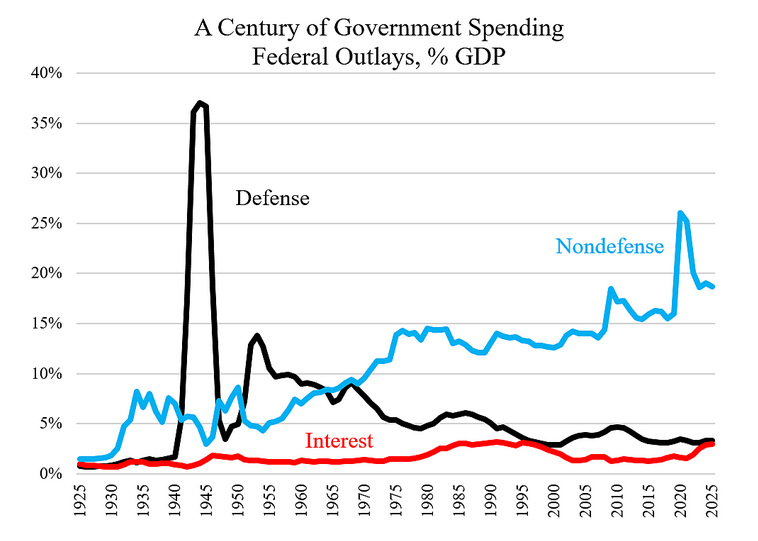

If we want to know why we’re so in debt, one has to look at the growth of non-defense spending:

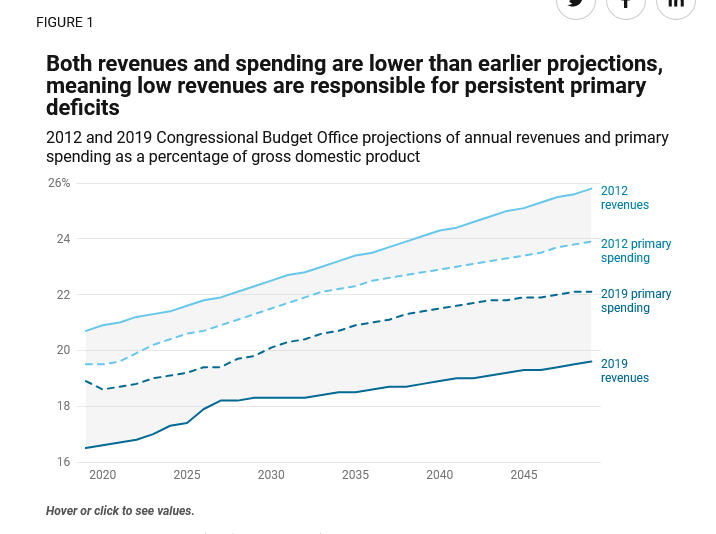

Zakaria and others on the left rely on the Congressional Budget Office’s projections that show if we didn’t cut taxes, receipts would grow to well over 20% of GDP, matching expenses. The fact that we have never experienced this outcome from past tax increases erodes any faith in the CBO projections. Given the CBO’s major flubs in the past, this is wise. Yet, the CBO has projected reaching over 20% of GDP if we raise taxes as the Obama administration proposed:::

Economist Art Laffer pointed out the fallacy of thinking that raising taxes by a certain amount will give you equal receipts. This kind of static thinking makes no sense. As Laffer pointed out, a zero and a 100% tax rate raise nothing. Of course, no taxes, no revenue. If you take everything, no one will do anything that the taxman can find. Somewhere in between is the sweet spot, maximizing revenues. The trick is to find it. The CBO’s static position of raising taxes by 10% results in 10% more revenue, ignoring that economies are dynamic.

The classic illustration is that a sweet spot raises more income than high taxes, as illustrated in the Clinton-era capital gains tax reduction. The CBO type static projection says you get less revenue, but revenue explodes, and the answer lies in how people respond. High taxes make people reluctant to sell, even if it might enhance their position in the future. A low tax opens up the possibility for people to make more transactions. If people don’t sell, the government gets no revenue, no matter how high the tax. Several low tax transactions increase the take, a dynamic response.

My point isn’t to make you a market or tax guru. Instead, it’s to point out how often we get information conforming to a particular narrative, rather than giving facts, experience-based, or logical information.

Zakaria probably knows of Art Laffer, but because the economist worked with Ronald Reagan, the left sees fit to ignore him. Larry Kudlow knows how detrimental tariffs can be. He only has to review his past positions. Yet, he gives possibly dangerous advice to his viewers. Both have large media platforms; they chose to promote their faction rather than speak the truth they know or should know.

I found these two this week. There will be others next week, and on and on—no wonder our divisions are growing wider.